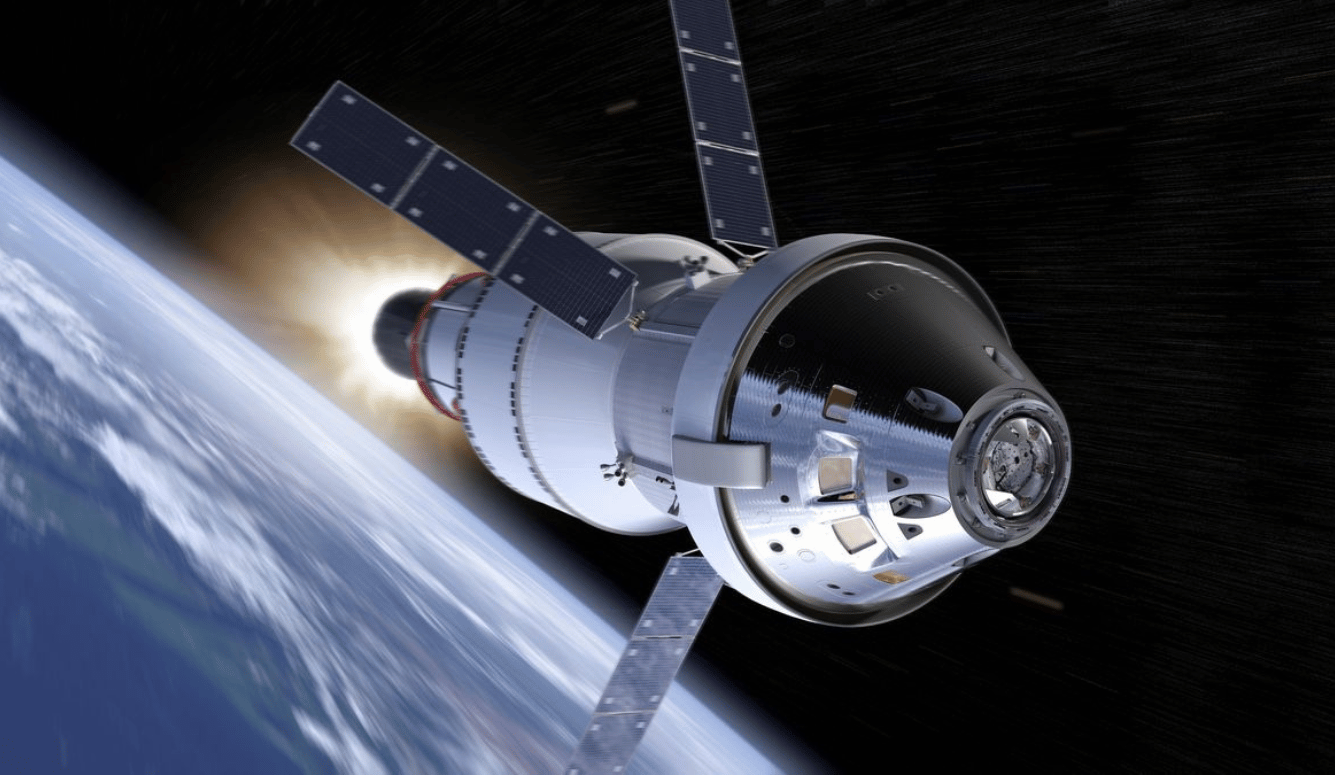

Last week two of the most powerful rockets ever flown were launched. On the 16th In January, SpaceX's Starship launched its seventh test flight and its first stage booster was successfully captured – although the upper stage was lost in rather spectacular fashion.

Success is uncertain, but entertainment is guaranteed! ✨

pic.twitter.com/nn3PiP8XwG— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) January 16, 2025

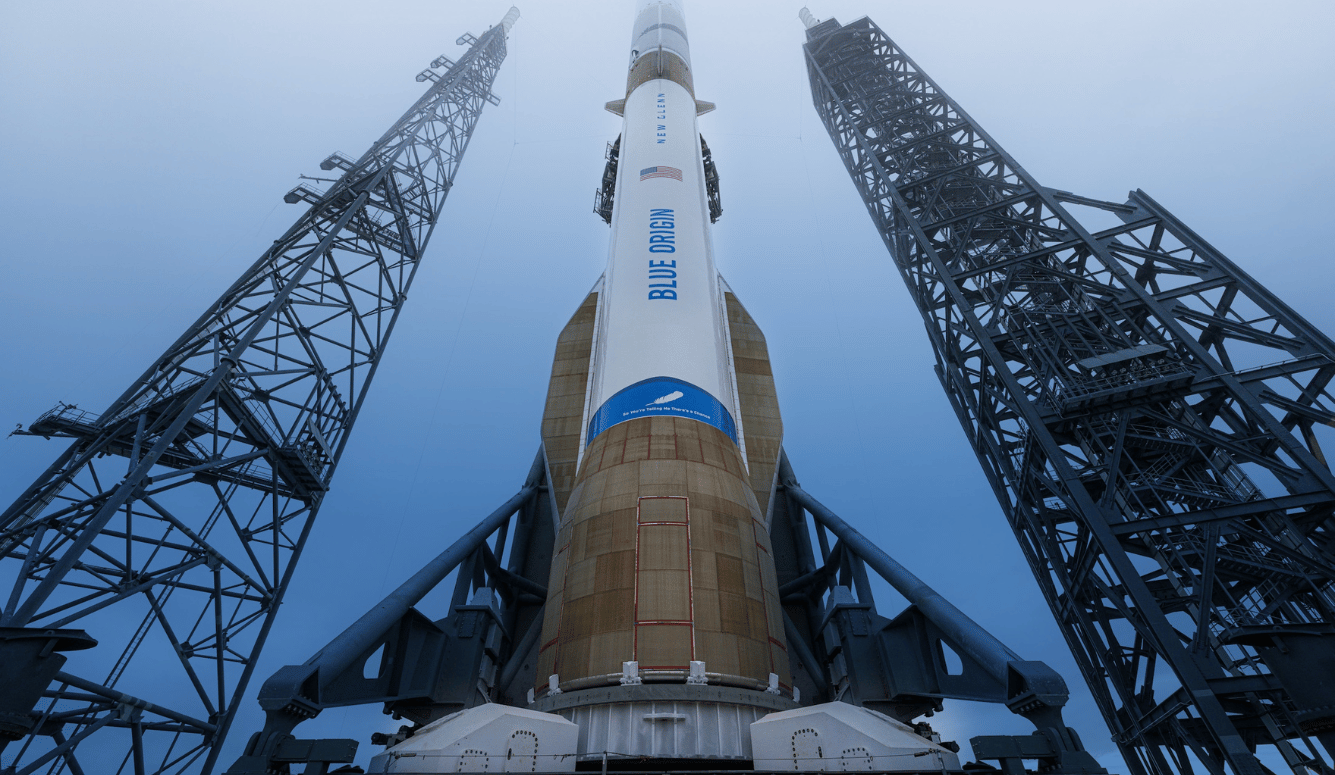

On the same day, New Glenn, the flagship of Jeff Bezos' space company Blue Origin, launched its maiden flight. Although the company's much smaller New Shepard vehicle has performed many suborbital flights, this is the company's first orbital vehicle. New Glenn is a similar vehicle to Falcon 9, but larger, and like Falcon 9, the first stage is designed for shipboard recovery. A recovery attempt was made on this first flight, but the booster was destroyed upon entry into the atmosphere. However, they are widely expected to achieve this on subsequent flights and become a competitor to SpaceX.

The launch of the new Glenn rocket was photographed from the ISS on January 16th. This shows New Glenn's upper stage in the coastal phase after booster separation. In this 4 minute exposure, New Glenn is seen as a faint streak moving from the bottom right to the top left as it crosses the brighter… pic.twitter.com/YwWtCfMoZt

– Don Pettit (@astro_Pettit) January 19, 2025

Blue Origin's entry into the reusable orbital rocket market has reignited popular interest in a multi-billion dollar space race between Elon Musk and Bezos – and sometimes Richard Branson – but in fact there is no such race – or at least things are not quite appear as they could be. Since Musk has been the most public about his plans, many people believe that these three men are in a race to get humans to Mars. But Jeff Bezos doesn't want to send people to Mars, as he emphasized in a speech at the George W. Bush Presidential Center in April 2018:

My friends who want to move to Mars? I say, “I have an idea for you. Why not climb the summit of Mount Everest for a year first? Because the summit of Mount Everest is a garden paradise compared to Mars.”

It's not difficult to figure out who this comment was directed at. Bezos is inspired by a vision that does that not involves life on Mars – or a planet other than Earth – but envisages humans inhabiting artificial worlds in open space. The concept dates back to the 1970s and the work of Gerard O'Neill.

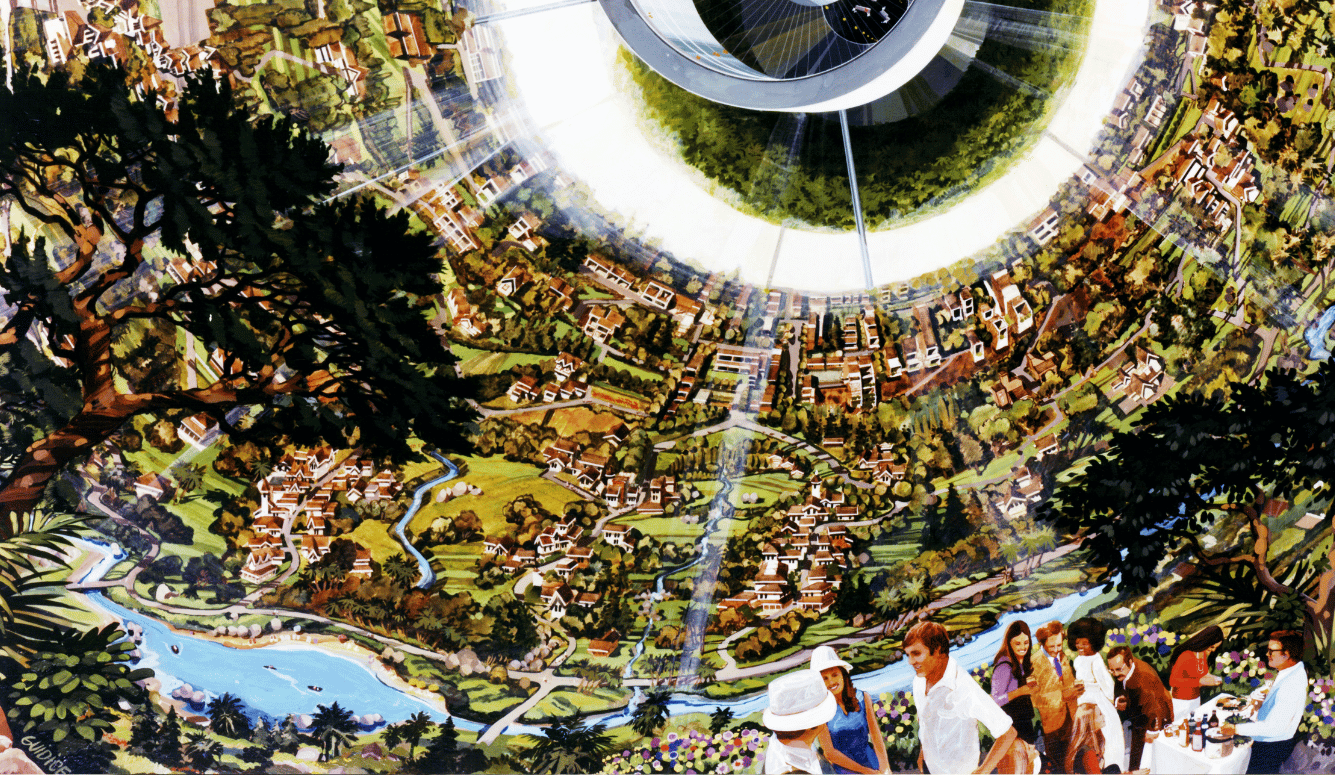

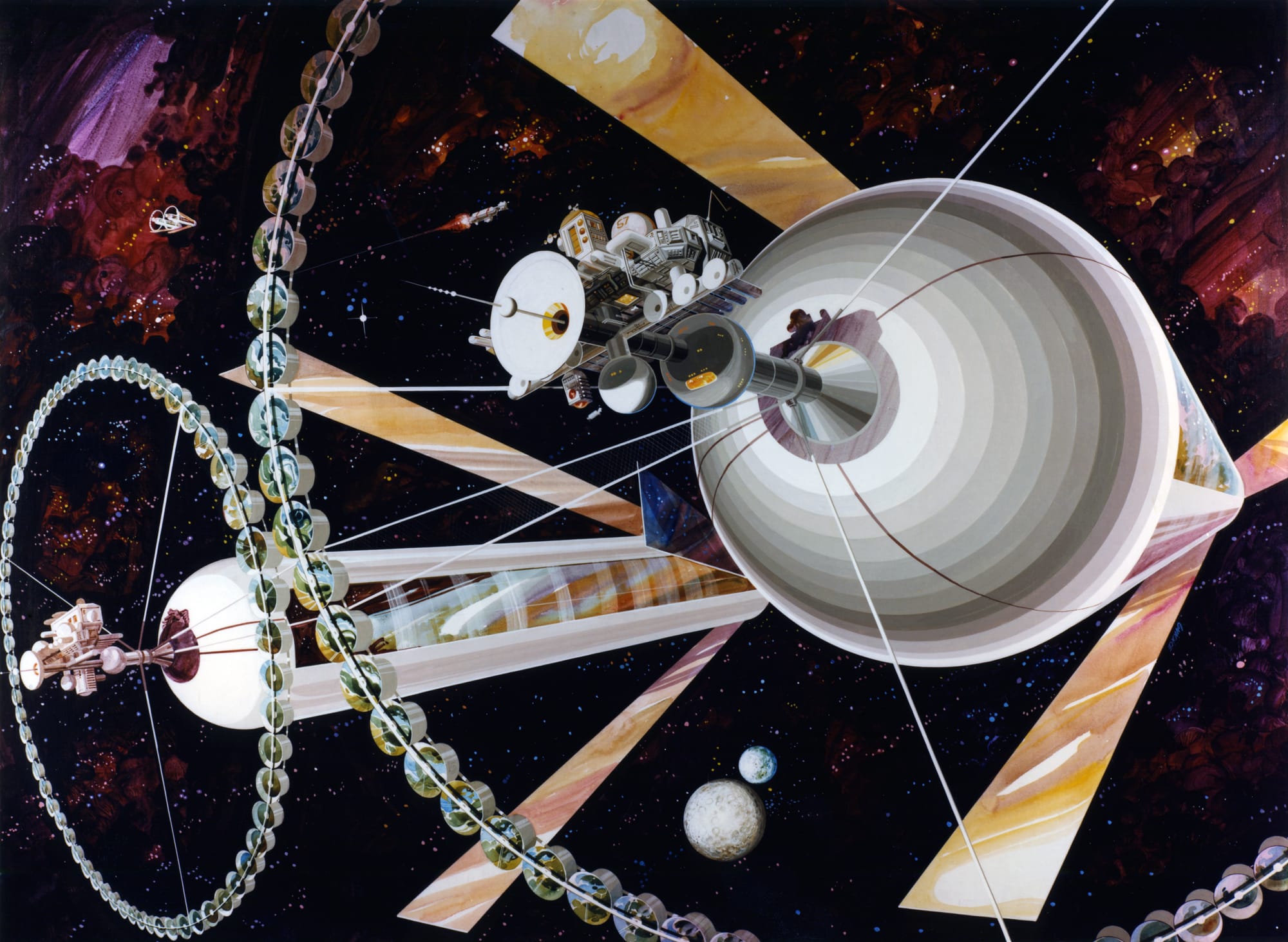

As a professor at Princeton, O'Neill and his students developed an alternative vision for space colonization in which habitats would be established at gravitationally stable points called Lagrange points near the Earth and the Moon and rotated so that the Centrifuge is created The force felt by the occupants would simulate gravity. Such stations would provide far more habitat than is available on any planetary surface in the solar system, and he therefore concluded that they would provide better sites for an expanding interplanetary civilization, in a departure from what Isaac Asimov jokingly called “planets.” “chauvinism” of science fiction.

O'Neill published a book entitled The High Limitwho fleshed out his ideas, and supported a NASA study that examined the practicality of building such a habitat. He was somewhat well known at the time, having been interviewed on television about his ideas, but despite his immense influence in the space community, he has since been largely forgotten by the general public. His concepts enjoyed brief popularity but then fell out of favor, both because of political attacks from critics who didn't like the idea of NASA spending money on such things, and because of the growing realization that the space shuttle was never going to be cheap , regular would provide access to space such a project would require.

Humanity's Space Future: Conflict or Cooperation?

The future is unwritten and a future of space cooperation and peaceful settlement remains possible.

But now everything is different. In 2024, SpaceX will launch more rockets in a single year than the Space Shuttle did in its entire thirty-year lifespan, and at a fraction of the cost per kilogram. Low-cost reusability — something that has always eluded the shuttle program — is key, and SpaceX, Blue Origin and other companies are hoping to make it possible. Concepts that were limited by launch costs a decade ago can now be seriously considered, including building habitats in space.

However, the amount of mass that must be moved into space to create such habitats is very large. To provide gravity through rotation, the speed of rotation must be kept low – 4 to 6 revolutions per minute is the likely maximum to which humans can adapt, and most designs aim to be lower to ensure that everyone can easily acclimatize – and to achieve gravity at earth level at this speed The rotation requires a large radius. The largest habitat proposed by O'Neill – which he referred to as his “Island 3” design but which has since become known as the eponymous “O'Neill Cylinder” – was 8 kilometers in diameter and 32 kilometers long, which allowed the rotation rate to be kept below 1 rpm. Such a habitat would have a mass of billions of tons, far too much to be launched from Earth even in the new age of low-cost launch vehicles.

O'Neill understood the problem and worked on a solution in the form of in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU. The vast majority of the mass required for space habitats would be sent not from the Earth but from the Moon. His plan, fleshed out in the NASA Space Settlements Study, was to build a mining facility on the moon and a device called a mass driver. This was a series of coils designed to accelerate containers of lunar regolith to escape velocity horizontally along the surface, taking advantage of the lack of air resistance to provide a very cost-effective launch system. O'Neill and his colleagues built a series of smaller prototypes of such a device and demonstrated them in the laboratory.

This is a key difference between O'Neill's vision and the Mars approach to space colonization: Once humans are placed on Mars, they can immediately begin building a base. Space habitats require significant upfront investment, but in return you get an environment much closer to that of Earth, and it's also closer, meaning people would be able to travel to and from the habitat within a matter of days during the trip to Mars takes about six months and the trips can only be carried out in time windows every 26 months.

Philosophically, the O'Neillian approach requires a little more patience, although its early proponents apparently did not realize this. When the concept was first proposed in the 1970s, proponents formed the “L5 Society” (named for the 5th Lagrange point near the Earth and Moon where the first colony would be located) to advocate for using the concept and championing slogans such as “Lunar Mine by '89″ and “L5 by '95”. However, humanity did not undertake any major infrastructure projects in space during the Seinfeld years. O'Neill's early supporters believed that NASA would provide the funding and that the shuttle and derivative hardware could complete the task in a twenty-year period, but both assumptions were far off the mark.

In the 1970s, it was widely assumed that the space shuttle would fly fifty times a year and that the cost per kilogram of orbit would be comparable to what we see with Falcon 9 today. Space colonization studies took this for granted at the time – after all, NASA had landed a human on the moon from scratch in less than a decade, so their promises of cheap routine access to space should be credible, right? In reality, the shuttle never managed more than nine flights per year and cost much more per kilogram than contemporary expendable launch vehicles. After the initial public outcry and some cooperation from NASA, the space colonization project faced severe and unjustified criticism from politicians, and NASA distanced itself from it.

The L5 Society's successor, the National Space Society, avoids such aggressive schedules. Bezos himself has spoken of building a “road to space” that would provide the next generation with the infrastructure to continue the project. He founded a “Club for the Future” to inspire children to take up the challenge where they left off. Blue Origin's own promotional material compares the effort to building a cathedral. However, this may be a conservative estimate of the time frame. Given recent advances in automation and manufacturing, there are reasons to believe that the use of space resources could accelerate faster than expected. Watch this space to see what Blue Origin and other companies investing in this space will achieve in the next few years.

Elon Musk, on the other hand, has no interest in the industrial development of the moon – a project he dismisses as a “distraction” from building a Mars base as quickly as possible. That makes sense given his goals, but it shouldn't stop Jeff Bezos or anyone else from pursuing an alternative path. The merits of these two competing plans to colonize space have been debated by engineers, scientists and advocates for decades, but now that there is real money behind attempts to implement both plans, the matter can be resolved through action. Whatever happens, the future in space will be incredible.