Factors may have a new tool in the fight against misinformation.

A team of Cornell researchers has developed a way to the “watermark” lamp in videos, with which they can determine whether video was fake or manipulated.

The idea is to hide information in almost invisible fluctuations of lighting on important events and locations such as interviews and press conferences or even entire buildings such as the United Nations headquarters. These fluctuations are designed in such a way that they remain unnoticed by humans, but are recorded in every video that was recorded under the special lighting as a hidden watermark that can be programmed in computer screens, photographer lamps and built -in lighting. Each watermark light source has a secret code with which the video tested according to the corresponding watermark and malicious processing is displayed.

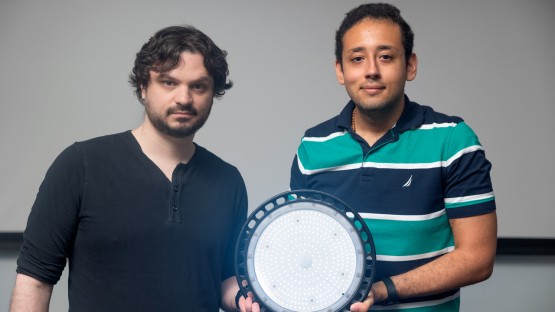

Peter Michael, a doctoral student in the field of computer science that headed the work, will present the study. “Noise -encoded lighting for forensic and photometric video”On August 10th in Siggraph 2025 in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Editing video material in a misleading way is nothing new. But with generative AI and social media, it is faster and easier to spread misinformation than ever before.

“In the past, video was treated as a source of truth, but that is no longer an assumption that we can do” ABE DavisAssistance professor of computer science at Cornell Ann S. Bowers College for computer and information science, which first presented the idea. “Now you can create pretty much a video of everything you want. It can be fun, but also problematic because it is only more difficult to say what is real.”

In order to clear up these concerns, the researchers had previously developed techniques to get digital video files directly to watermarks, with tiny changes to certain pixels to identify unmanipulated film material or can determine whether a video was created by AI. However, these approaches depend on the video manufacturer, which uses a certain camera or a KI model -a level of conformity that may expect unrealistically to expect potential bad actors.

By embedding the code in the lighting, the new method ensures that each real video of the subject contains the secret watermark, regardless of who has recorded it. The team showed that programmable light sources such as computer screens and certain types of space lighting can be encoded with small software, while older lights, how many leading lamps can be encoded by attaching a small computer chip using the size of a postage stamp. The program on the chip varies the brightness of the light according to the secret code.

What secret information is hidden in this watermark and how does it show when video is fake? “Each watermark has a temporally stamped version of the unmanipulated video under slightly different lighting. We call these code videos,” said Davis. “When someone manipulates a video, the manipulated parts contradict what we see in these code videos, and so we see where changes have been made. And when someone tries to generate a wrong video with AI, the resulting code videos simply look like random variations.”

Part of the challenge in this work was to be largely not perceptible for humans. “We used studies from human perception literature to inform our design of the coded light,” said Michael. “The code is also designed in such a way that it looks like random variations that already appear in light as” noise “, which also makes it difficult to recognize it unless they know the secret code.”

When an opponent breaks off the footage like from an interview or a political speech, a forensic analyst can see the gaps with the secret code. And when the opponent adds or replaces objects, the changed parts usually appear black in recovered code videos.

In the same scene, the team successfully used up to three separate codes for different lights. With each additional code, the patterns become more complicated and more difficult to fake.

“Even if an opponent knows that the technology is used and somehow the codes find out, his job is still much more difficult,” said Davis. “Instead of making the light for just one video, you have to falsify every code video separately, and all of these counterfeits have to agree.”

You also checked whether this approach works in some surroundings outdoors and in people with different skin tones.

However, Davis and Michael warn that the fight against misinformation is a arms race, and the opponents will continue to develop new ways to deceive.

“This is an important problem,” said Davis. “It will not disappear, and in fact it only gets more difficult.”

Zekun Hao, Ph.D. '23, and Serge belongs to the university of Copenhagen co-authors of the study.

The work was partially supported by a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship and the Pioneer Center for AI.

Patricia Waldron is the author of Cornell Ann S. Bowers College for Computer and Information Science.